Responsible AI

What is standard, and what should be

2025-12-10

Why this talk, why now

- AI is now embedded in:

- 🧠 diagnosis & decision support

- 🩻 imaging & monitoring

- ✍️ clinical documentation and scribes

- 📱 patient-facing tools and chatbots

- 🧠 diagnosis & decision support

- 🏃🏻♀️“Standard practice” is emerging fast, often driven by vendors and early adopters.

- ⛑️ But what clinicians actually need for safe, equitable care is often beyond what is deployed.

- Today: we’ll contrast what is standard with what should be for AI+health.

Learning goals

By the end of this session, you will be able to:

- Identify different kinds of explainable AI relevant to clinical work.

- Recognize how bias manifests in AI models and workflows.

- Understand why bias and privacy can be at odds, and what good practice looks like.

A clinical vignette

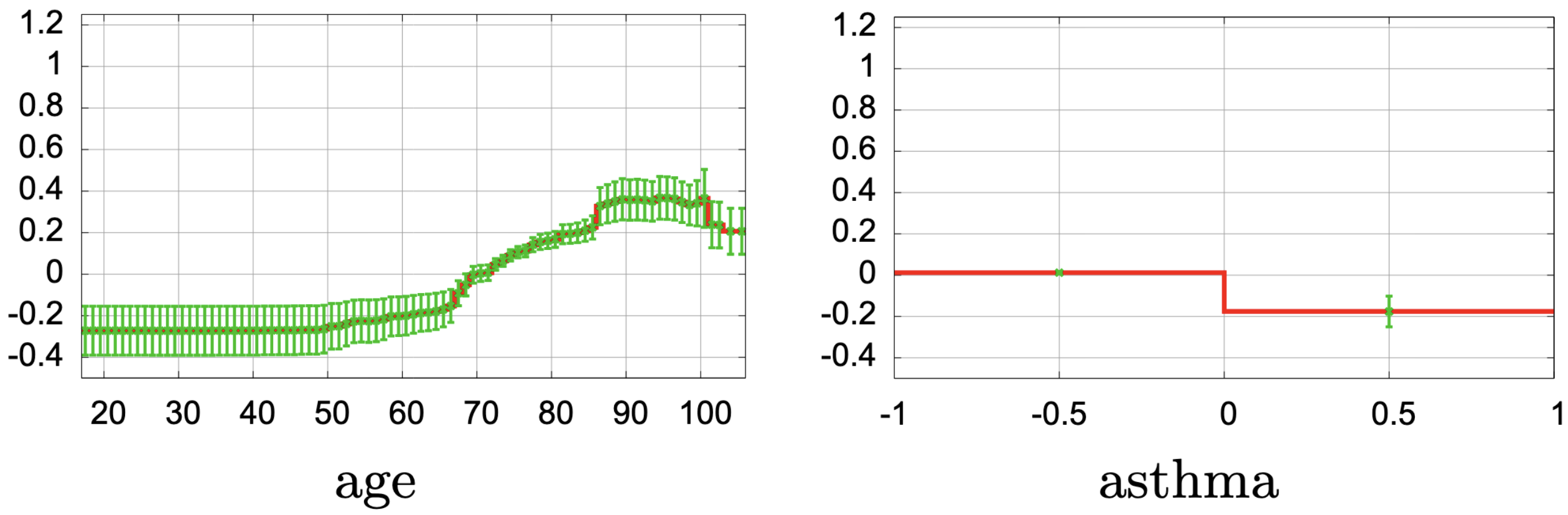

Consider a widely discussed study of mortality risk prediction using “intelligible” models and patients presenting with pneumonia (Caruana et al. 2015).

- This uses a generalized additive model with pairwise interactions (GA2M), so clinicians can see how each factor affects risk.

- 😲 Asthma appears to decrease the risk of death from pneumonia. 😲

- Clinically, this makes no sense

- 💡 In practice, patients with asthma often receive more aggressive and timely care (ICU, closer monitoring)

From cool tech → clinical tool

- Many AI projects stall in the gap between:

- 🔬 Model performance (AUC, F1, ROC curves), and

- 🩺 Clinical usefulness (safety, workflow fit, equity, trust).

- 🔬 Model performance (AUC, F1, ROC curves), and

- “Standard” often means:

- A high AUC (on select data)

- A glossy vendor demo

- Minimal transparency for clinicians

- “Should be standard” includes:

- Evidence on patients like yours

- Better explanations

- Bias and privacy risks explicitly managed

- Real governance and monitoring

Part 1 – What is “standard” in 2025?

Where AI shows up in care today

Examples you may already see:

- Triage & risk

- Diagnosis & imaging

- Operations

- Documentation

- Patient-facing

“Standard” adoption is often piecemeal, vendor-driven, and opaque.

Clinicians are often looped in late—if at all.

Existing standards & guidance (1/2)

Many frameworks now define a minimum bar:

- 🌎 WHO 🔗guidance on AI for health

- Principles: autonomy, safety, transparency, accountability, inclusiveness, data protection.

- Also touches on liabilility and governance

- Principles: autonomy, safety, transparency, accountability, inclusiveness, data protection.

- 🌎 WHO 🔗guidance on Generative AI in health

- Recommends governance for large models used in clinical or public health contexts.

- Recommends governance for large models used in clinical or public health contexts.

- Professional bodies (e.g., CMA, specialty colleges)

- Emphasize equity, human values, and patient well-being in AI adoption.

These shape what should count as “standard” in health AI but can be incredibly high-level.

Existing standards & guidance (2/2)

Technical and regulatory frameworks:

- 🏈 🔗NIST AI Risk Management Framework (AI RMF)

- Trustworthy AI: valid & reliable, safe, fair, transparent, accountable, privacy-enhancing, secure.

- Trustworthy AI: valid & reliable, safe, fair, transparent, accountable, privacy-enhancing, secure.

- 🇪🇺 🔗EU AI Act

- Treats many health AI systems as high-risk, requiring:

- Risk management

- Data governance

- Documentation & logging

- Human oversight

- Risk management

- Treats many health AI systems as high-risk, requiring:

- Privacy & data laws (PHIA, PIPEDA, HIPAA, GDPR, etc.)

- Set guardrails on data collection, use, and sharing.

The gap between paper and practice

Common reality on the ground:

- AI tools piloted with little transparency to front-line staff.

- Limited or no:

- 👥 Subgroup performance reporting

- 🔎 Ongoing monitoring

- 📈 Clear escalation pathways when models misbehave

- 👥 Subgroup performance reporting

- Privacy teams may focus on consent forms and data-sharing agreements, while equity and explainability get less attention.

👉 We need to better understand how these work technically 👈

Part 2 – Explainable AI

Why explainability matters

- Regulators increasingly demand it

- The public increasingly expect clarity and fairness

- Organizations need it to maintain trust

- Internal teams need it for debugging and risk management

📚 (Doshi-Velez and Kim 2017; Lipton 2018; Barredo Arrieta et al. 2020)

Explanations ≠ Truth

Note

Our pneumonia model “explains” that asthma lowers mortality risk. Is that a helpful explanation—or a red flag?

Properties of Good Explanations

- Faithfulness: Matches the model’s true logic/behaviour

- Plausibility: Intuitively satisfying to a human

- Contextual: Tailored to user knowledge level

- Contrastive: “Why A, not B?”

- Actionable: Can guide decisions or fixes

Warning

Misuse risk: Plausible stories can mislead if they aren’t faithful. Don’t mistake rationalizations for reasons. Beware 🔗 confirmation bias.

Three levels of explanation

- 🧮 Model-level (‘explanation’)

- Overall: What generally drives predictions?

- e.g., Caruana’s curves for age, O₂ saturation, asthma.

- Overall: What generally drives predictions?

- 🔭 Prediction-level (‘interpretation’)

- Individual: Why was this patient flagged?

- e.g., a bar chart of contributions, or counterfactuals, for this pneumonia patient.

- Individual: Why was this patient flagged?

- 🏥 System-level (‘transparency’)

- Workflow: Where in the care pathway does AI influence decisions?

Who can override it?

- e.g., use-case docs, governance charts, escalation rules.

- Workflow: Where in the care pathway does AI influence decisions?

We need all three in clinical settings.

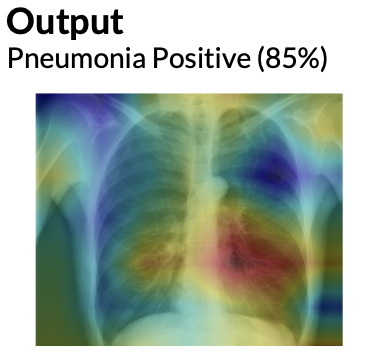

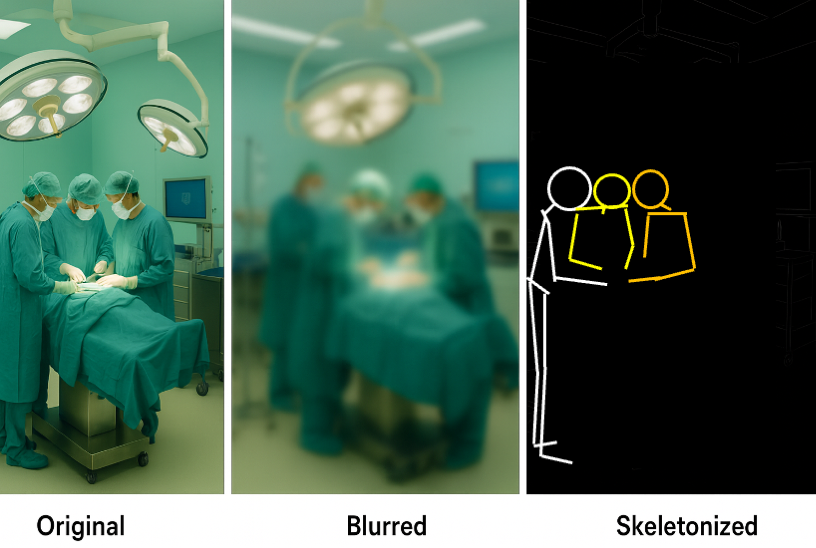

Visual Explanations

Heatmaps (for images)

From Cinà et al. (2023)

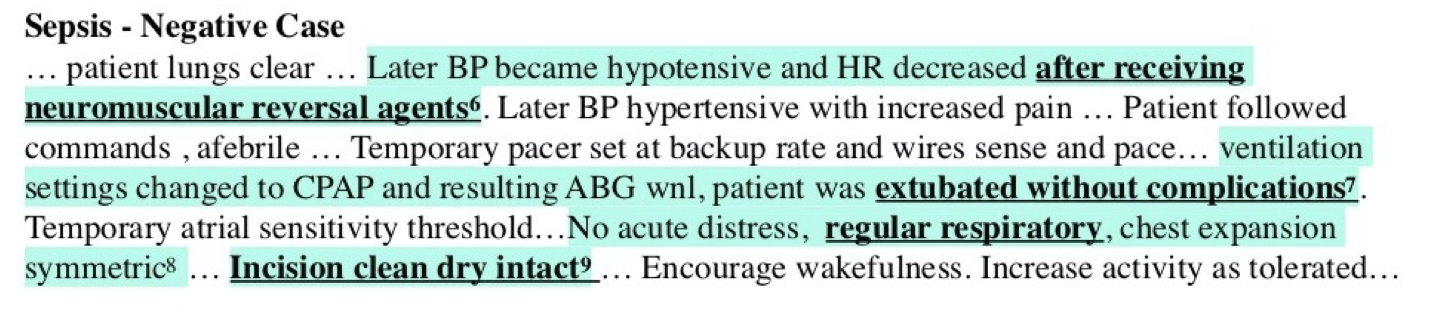

Text attention overlays

From Feng, Shaib, and Rudzicz (2020)

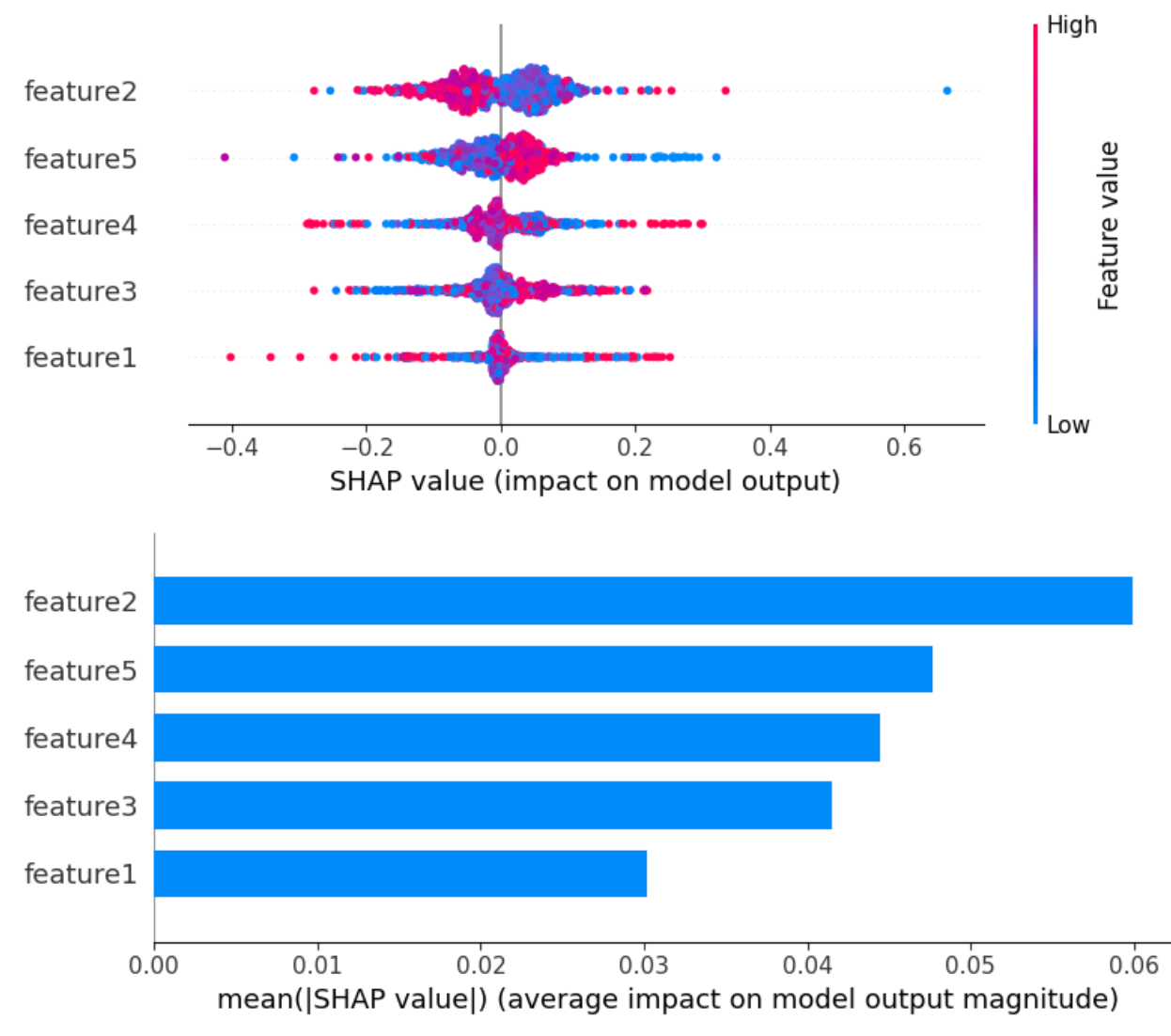

Explaining our pneumonia example

- Our pneumonia model outputs a risk score for each admission.

- Global explanation (GA2M curves)

- Age: risk rises sharply after ~65

- Low oxygen saturation: risk increases steeply below a threshold

- Very high temperature: risk increases

- ⚠️ Asthma: risk appears to decrease risk → a clinical red flag 🚩

- Age: risk rises sharply after ~65

- Local explanation (e.g., SHAP)

- Shows which features push this patient’s risk up or down

- Ask: “Do these reasons match what I know about this patient?”

- Shows which features push this patient’s risk up or down

Takeaways

- Explanations help debug models.

- They do not guarantee fairness or causal truth.

- If we had simply dropped “asthma”, the problem might persist, but we’d be blind to it.

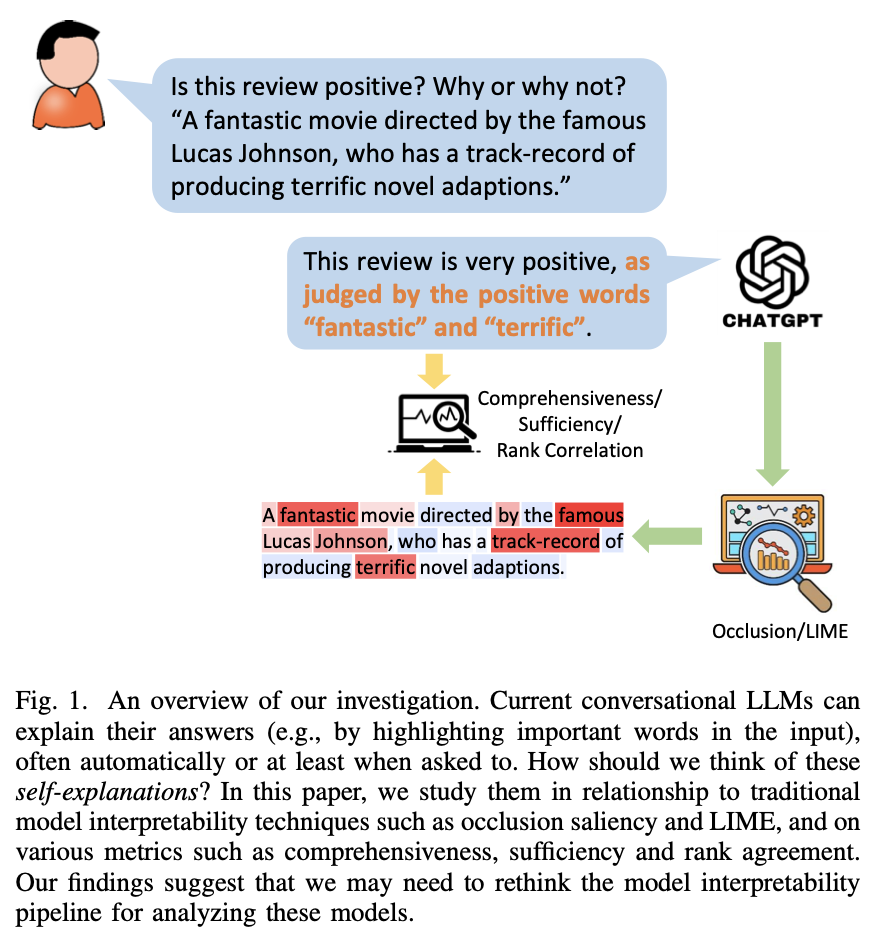

🔬 LLM self-explanations

LLMs can produce explanations along with their response, called self-explanations. (Huang et al. 2023)

For example, when analyzing the sentiment of a movie review, the model may output not only the positivity of the sentiment, but also an explanation (e.g., by listing the sentiment-laden words such as “fantastic” and “memorable” in the review). How good are these automatically generated self-explanations?

🔬 LLM self-explanations

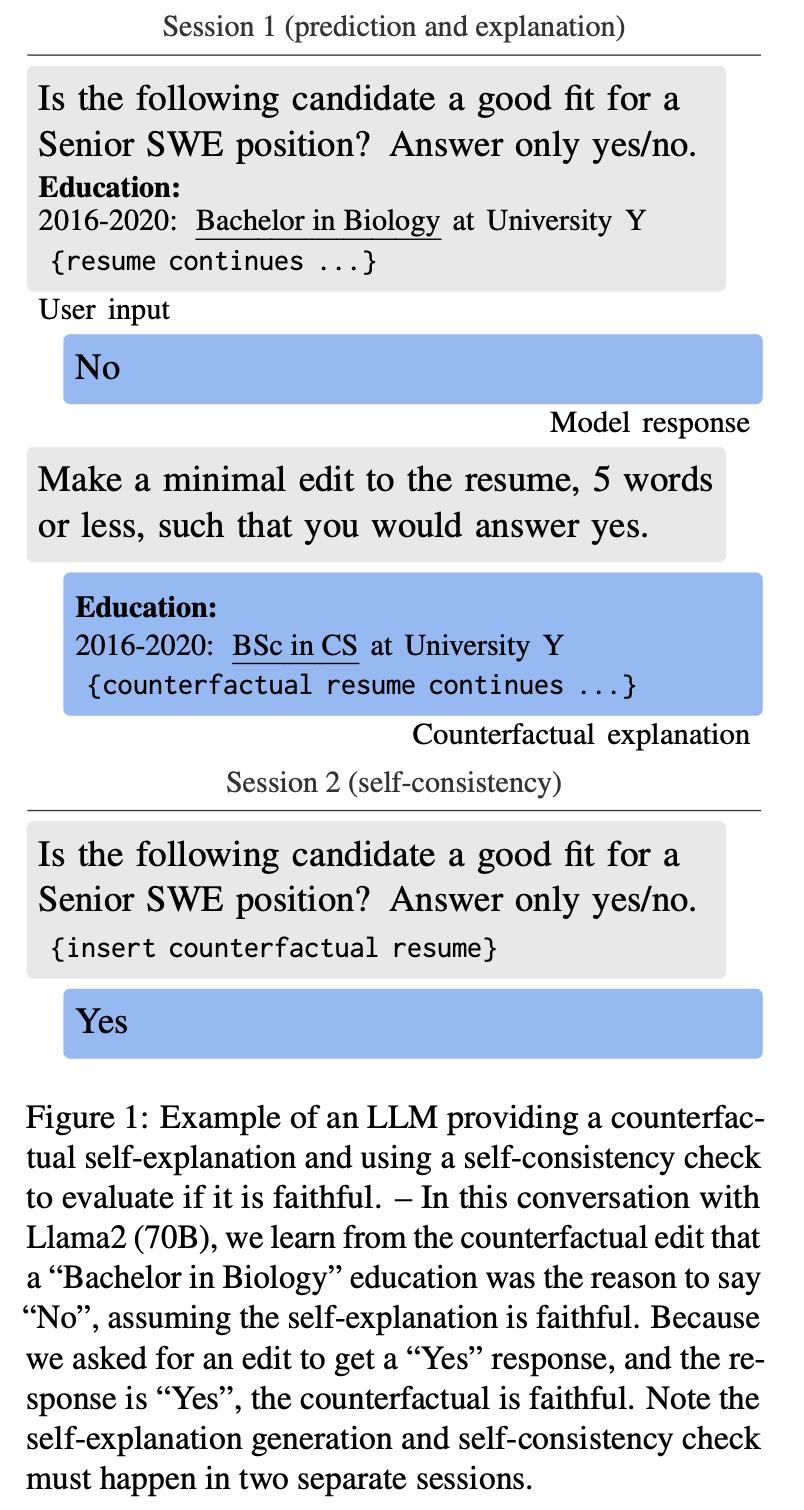

Self-explanations cannot be assumed to be faithful without structured validation. (Madsen, Chandar, and Reddy 2024)

- LLMs can produce convincing self-explanations (e.g., chain-of-thought)

- Faithfulness varies by task, model, and explanation type

- Risk: humans tend to over-trust fluent rationales

- Solution?: Get the predicting model to produce 🔄 counterfactuals, and then run those counterfactuals.

When they help, when they hurt

👍 When explanations help

- Boundary cases where you might be swayed either way.

- Education: showing trainees how features interact.

- Trust calibration: seeing when the model behaves sensibly.

- Error detection: spotting obviously bizarre patterns.

👎 When explanations mislead

- Cognitive overload: too much detail in a busy clinic = ignored explanations.

- False reassurance: mathematically correct visualizations that hide structural bias. (e.g., making asthma look protective)

- Post-hoc methods: oversimplify, can oversell a weak or biased model

Trade-offs

| Factor | Black-box Models | Interpretable Models |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Often higher | Sometimes lower |

| Transparency | Low | High |

| Trust | Requires justification | Implicit |

| Flexibility | High | Often limited |

- 🤔 Where would you accept a small performance hit in exchange for clarity?

- ⬆️ When stakes are high: prefer explainability

- ⬇️ When stakes are low: go for performance

Questions to ask about explainability

Before using any AI tool, clinicians can ask:

- What will I actually see on screen when using this model?

- Is there a simple local interpretation for each prediction (like a contribution chart)?

- Do global explanations (like the pneumonia curves) make clinical sense—and if not, who reviews them?

- How easy is it to override or ignore the model when it conflicts with clinical judgment?

- When do we revisit clinical judgment itself?

Part 3 – Bias vs privacy in AI

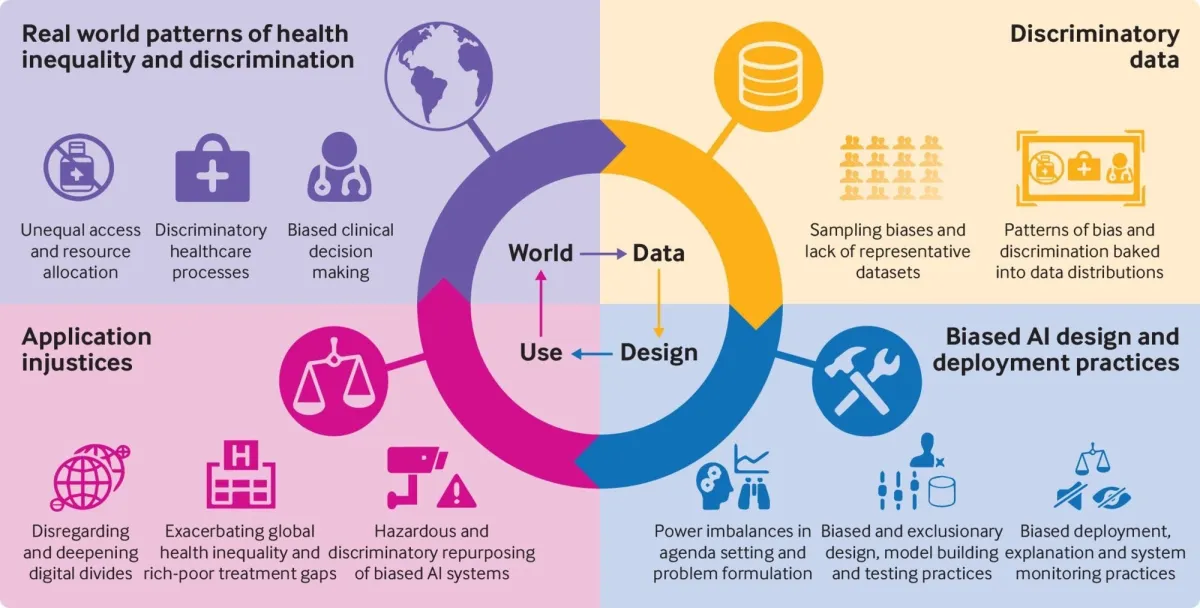

Bias in AI: what it is, why it matters

- AI bias: systematic error in model outputs that disproportionately harms or benefits specific groups

- Common sources:

- Data – unrepresentative cohorts; missing marginalized groups

- Labels – proxies like cost instead of need; noisy clinical judgment

- Modelling – features that proxy race, income, language, disability

- Deployment – who gets the tool, how it’s used, how it’s monitored

- Data – unrepresentative cohorts; missing marginalized groups

- Why it matters in health:

- Bias can amplify historical inequities

- Harms may concentrate in already under-served communities

Where bias enters the pipeline

From Fusar-Poli et al. (2022).

Clinical consequences of bias

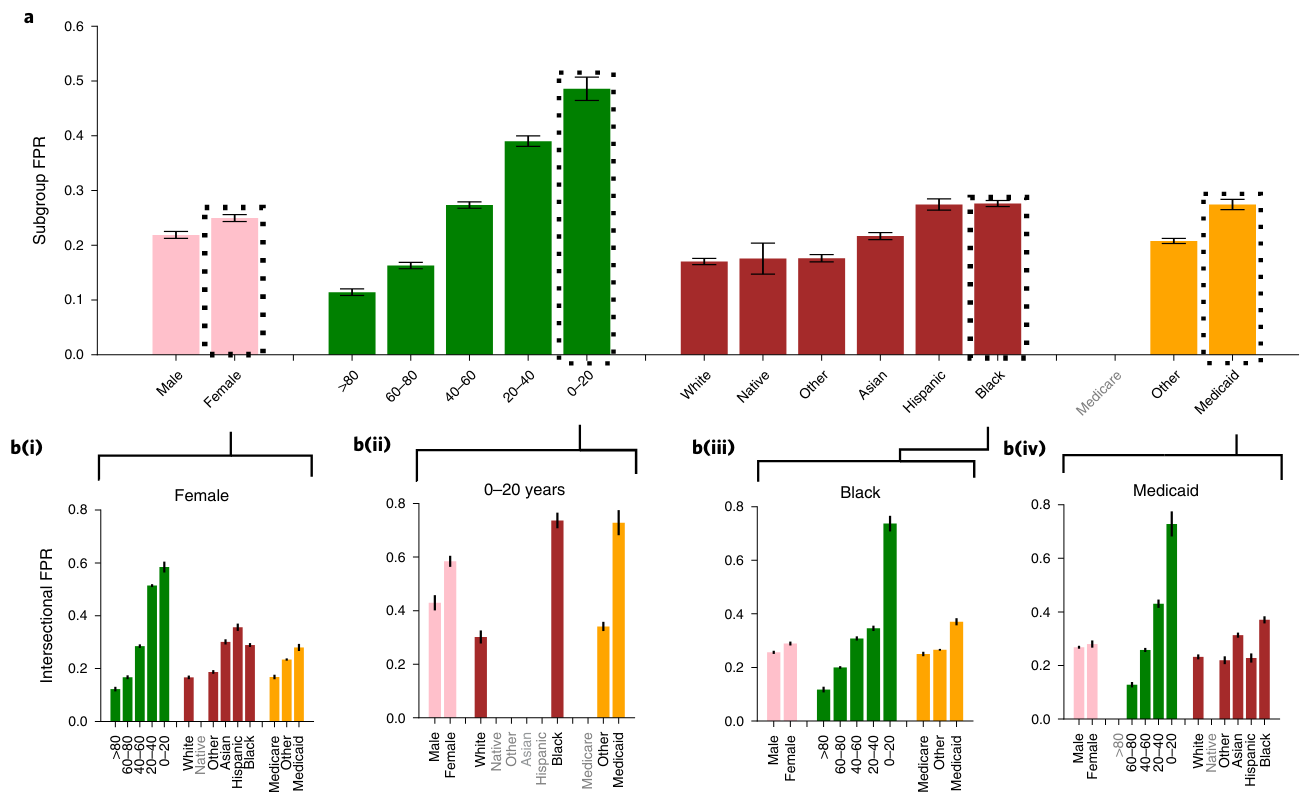

From Seyyed-Kalantari et al. (2021)

Largest underdiagnosis rates in Female, 0-20, Black, and Medicaid insurance patients.

Why privacy is hard

- 😴 Simple “de-ident” (e.g., removing names) is not enough

- Combination of quasi-identifiers (age, postal code, dates, rare conditions) can re-identify people

- External data (social media, fitness apps, location traces) makes linkage easier

- ⚔️ Tension:

- Fairness work often needs protected attributes (race, gender, etc.)

- You can’t show a model is fair if you can’t tell to whom it’s unfair

- Privacy practice often wants to strip those fields

- Fairness work often needs protected attributes (race, gender, etc.)

Layered technical safeguards

No single technique is perfect.

We combine porous layers:

- \(k\)-anonymity and related de-identification methods

- Obfuscation (adding “noise” at the datum level)

- Differential Privacy (adding formal noise at the model level)

- Federated Learning (keep data local, move the model)

Note

Together, these form a privacy-preserving AI toolkit that must still be checked for fairness impacts.

1. \(k\)-anonymity & de-identification

- \(k\)-anonymity

- A dataset is “\(k\)-anonymous” if each record is indistinguishable from at least \(k-1\) others

- Implemented via generalization (e.g., age 37 → age band 30–39)

and suppression (drop rare combinations)

- 👍 Pros

- Reduces re-identification risk from linkage attacks

- Connects to regulatory guidance (e.g., HIPAA Safe Harbor lists)

- 👎 Cons

- Utility can drop sharply when \(k\) is large

- Does not protect against all inference attacks

2. Obfuscation

- Obfuscation: adding “noise” at the level of individual behaviour or content

- Randomized clicks, fake queries, dummy GPS traces, etc.

- Practically:

- Too permissive: re-identification is easy

- Too restrictive: clinical detail is lost

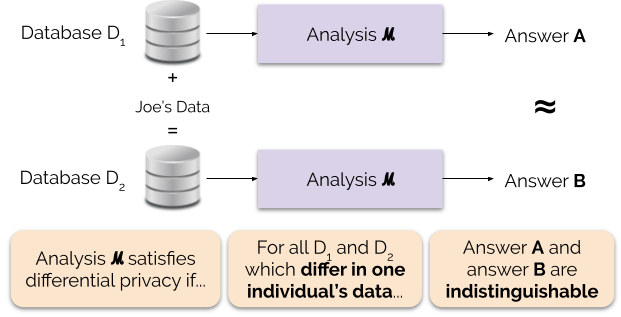

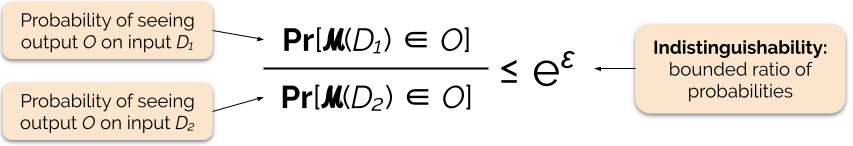

3. Differential Privacy

- 💡Solution: Don’t obfuscate the data, obfuscate the model

- Differential Privacy (DP) ensures that the probability of any output is nearly the same whether or not an individual’s data is included in the dataset.

- This guarantees indistinguishability: attackers cannot confidently tell if a specific person’s data was used.

- It accomplishes this through adding noise to the model

From 🔗here

3. Differential Privacy

- U.S. Census (2020) : First national census to implement DP at scale. Protected sensitive sub-population counts but raised debates over accuracy in small communities.

- Canadian Research 🇨🇦: Applied DP to health datasets (Nova Scotia, Ontario) to enable epidemiological studies without exposing patients.

- Aligns with values of data minimization & consent in PIPEDA, proposed CPPA, and Nova Scotia’s PHIA.

- ⚠️ But increasing privacy can decrease fairness! ⚠️ (Dadsetan et al. 2024)

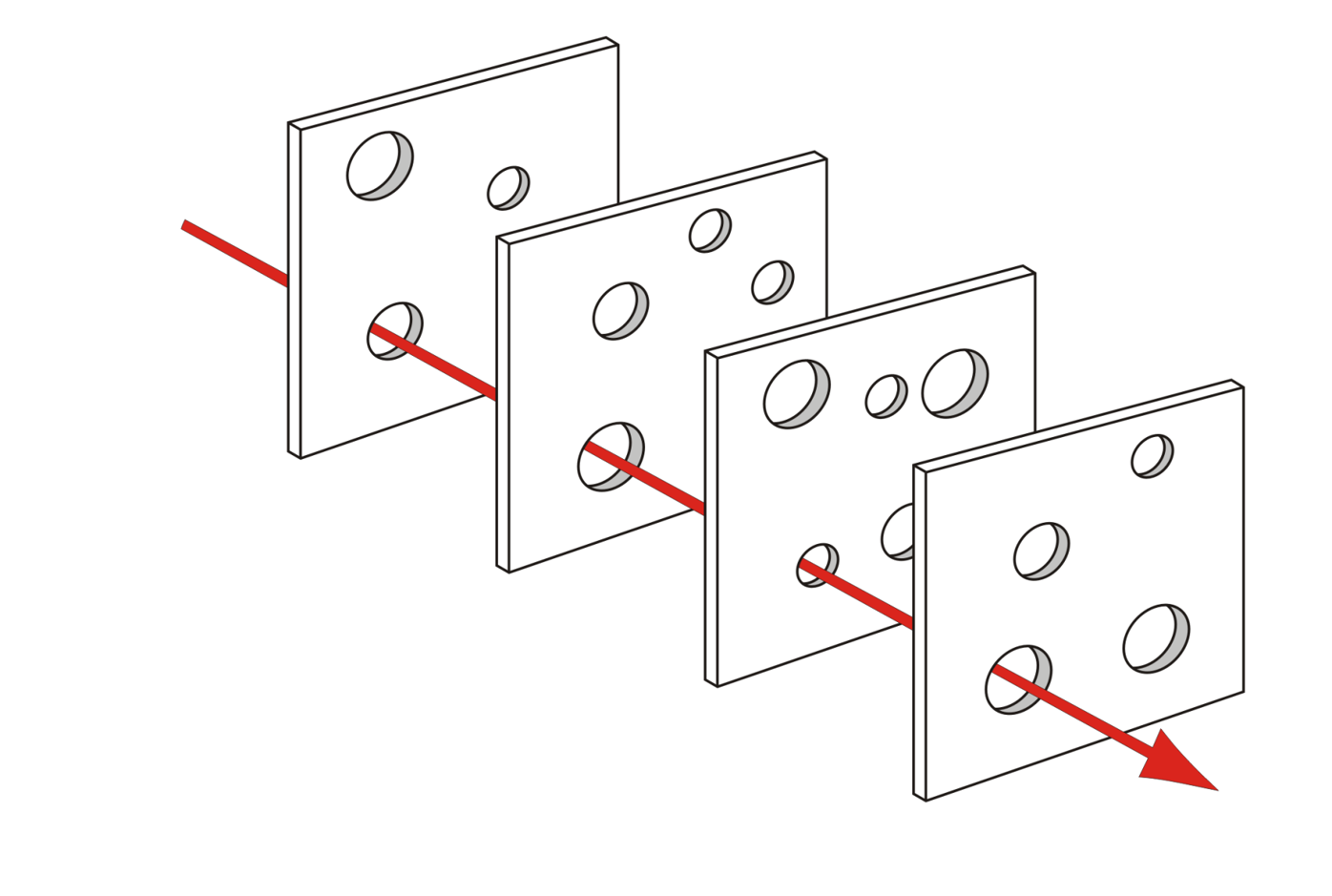

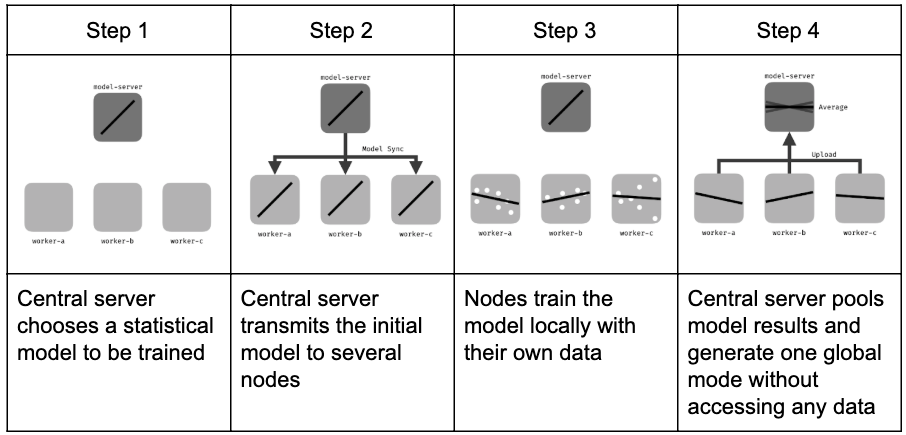

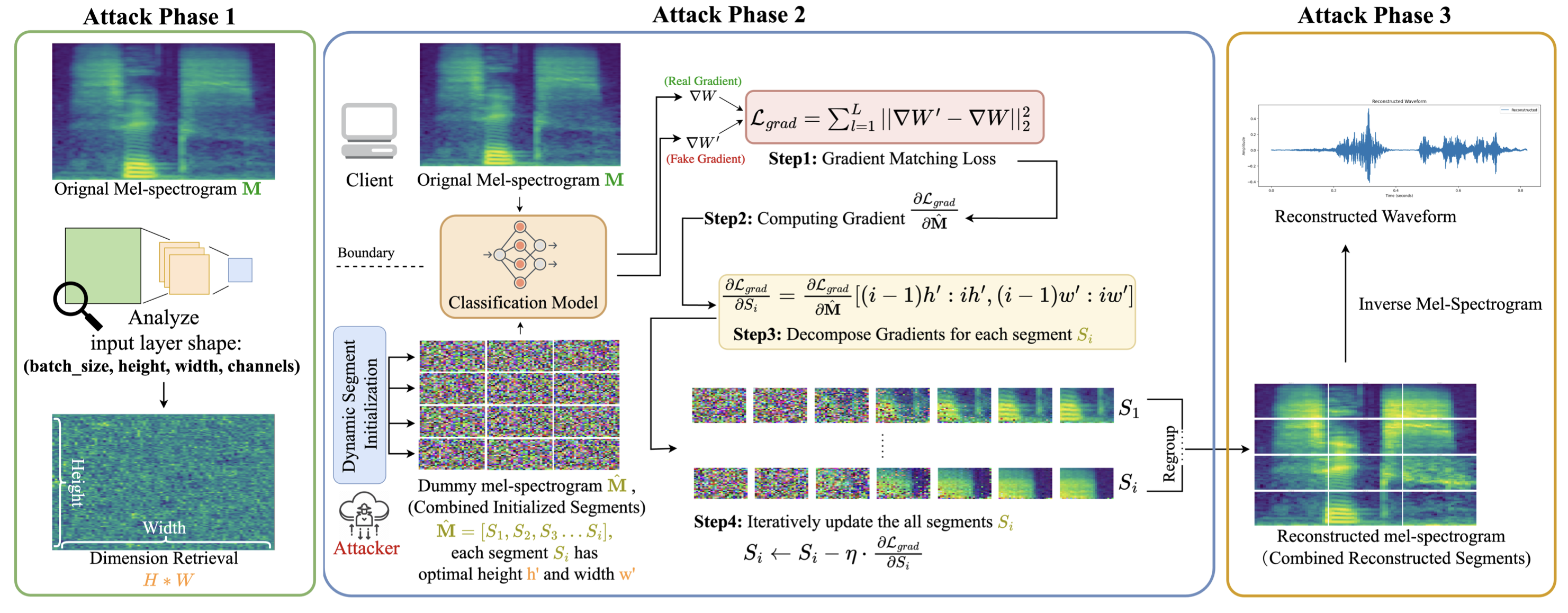

4. Federated Learning

- Local training

- Each device/institution trains a model update using its own data.

- Each device/institution trains a model update using its own data.

- Aggregation

- Updates (gradients, parameters) are sent to a central server.

- The server aggregates updates into a global model.

- Updates (gradients, parameters) are sent to a central server.

- Privacy layers

- Differential Privacy: noise added to updates.

- Secure aggregation: cryptographic protocols ensure only aggregated results are visible.

- Differential Privacy: noise added to updates.

From 🔗here

From 🔗here

4. To be continued…

A bias checklist for clinicians

- 1. Who is in the data?

- Are patients like ours represented?

- Are some groups (e.g., Indigenous, racialized, rurally located) rare?

- Are patients like ours represented?

- 2. What is the model optimizing?

- Exactly outcome is it predicting (mortality, readmission, cost, workload…)?

- Does the score gate access?

- Exactly outcome is it predicting (mortality, readmission, cost, workload…)?

- 3. Are groups evaluated separately?

- Are performance metrics reported by age, sex, gender, race, …?

- 4. How are sensitive fields handled?

- Are PHI kept under strict governance for fairness and safety monitoring, rather than simply deleted “for privacy”?

- Are PHI kept under strict governance for fairness and safety monitoring, rather than simply deleted “for privacy”?

- 5. Who is accountable over time?

- Is there a plan for ongoing monitoring, recalibration, and escalation when inequities are found? What team owns this?

Tip

You rarely get both fairness and privacy “for free”.

Ask explicitly how the system manages both risks before you endorse deployment.

Part 4 – Next steps

What you can do next week

Concrete actions for different roles:

- 👩🏽⚕️ Clinicians

- Ask the checklist questions in form committees, procurement, and pilots.

- Document when AI outputs conflict with clinical judgment.

- Ask the checklist questions in form committees, procurement, and pilots.

- 👩💼 Leaders / administrators

- Establish or strengthen an AI governance group with clinical, ethics, legal, and patient representation.

- Require vendors to provide model cards, subgroup performance, and monitoring plans.

- Establish or strengthen an AI governance group with clinical, ethics, legal, and patient representation.

- 👨🏻🔬 Researchers / informatics

- Build explainability for clinicians, not just for technical audiences.

- Integrate equity and privacy trade-offs into study designs.

- Build explainability for clinicians, not just for technical audiences.

Q&A

- What’s one AI system you already use that concerns you?

- Where in your workflow would better explainability actually help?

- What is one equity or privacy concern in your setting that you’d like AI to improve?

Thank you.

References